This series of short and to-the-point chapters is intended for international legal practitioners who have a nexus to Germany without being fully trained in German law. It is meant to provide a general overview of the structures, functioning, and general principles of German civil procedure. A new chapter will be published monthly.[1]

Germany is a civil-law country that has a substantial number of quirks and features in its rules of civil procedure distinguishing it from common-law countries and also from other civil-law countries. Foreign practitioners who deal at times with German law should be aware of these characteristics when facing litigation in Germany or contemplating choosing German courts as a dispute-resolution forum.

This first chapter will cover the basic structure of the German court system with a focus on the organization and functioning of the civil courts. It will also lay a foundation for our future chapters covering German civil litigation in greater depth.

General Structure of the German Court System

In contrast to many other countries, Germany does not have one single highest court that ensures a uniform application of the laws across all areas. Rather, German courts are divided into five branches, each having its own highest court. According to Art. 95 (1) of the German Constitution (Grundgesetz), these branches and their respective highest courts are:

- Ordinary courts (civil and criminal law): Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof);

- Administrative courts: Federal Administrative Court (Bundesverwaltungsgericht);

- Tax courts: Federal Finance Court (Bundesfinanzhof);

- Labor courts: Federal Labor Court (Bundesarbeitsgericht); and

- Social courts: Federal Social Court (Bundessozialgericht).

Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) rules solely on matters of constitutional law. Although the Federal Constitutional Court is often described as Germany’s highest court, it does not act as appellate court for the five top-of-their-branch courts. Recourse to the Federal Constitutional Court is generally available only if the applicant can demonstrate that its fundamental constitutional rights have been breached or that the decision of the lower court is based on an unconstitutional law.

There is also a Federal Patent Court, which hears certain intellectual property (IP) matters. Appeals against its decisions go before the Federal Court of Justice. Therefore, the Federal Patent Court is considered part of the “ordinary courts” branch.

The highest courts of the five German court branches, the Federal Constitutional Court, and the Federal Patent Court are all federal courts. Unlike, e.g., the U.S. system, Germany does not have distinct federal and state court systems. All lower-instance courts are courts of the 16 federal German states. Like the highest federal courts, the lower-instance state courts are divided into the five branches described above. The distinction between federal and state courts is mainly one of organizational responsibility, including funding, but is otherwise of no importance to the conduct of litigation in Germany. Both state and federal courts apply the same procedural and—with certain limited exceptions—substantive law. Separately, each German state has its own State Constitutional Court which rules on matters concerning the respective state’s constitution.

The Civil Branch of the Court System

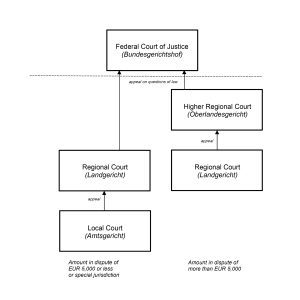

For historic reasons, there is no distinct “civil branch” among the five branches described above. Instead, courts for civil and criminal matters form the branch of the so-called “ordinary courts” (ordentliche Gerichtsbarkeit). The organization of the ordinary courts is governed by the Courts Constitution Act (Gerichtsverfassungsgesetz, GVG). Civil Procedure in Germany is predominantly governed by the Code of Civil Procedure (Zivilprozessordnung, ZPO). The ordinary court system in each state consists of—from lowest to highest—Local Courts (Amtsgerichte), Regional Courts (Landgerichte), and Higher Regional Courts (Oberlandesgerichte), with limited exceptions in name and organization in some states (e.g., Bavaria). The Federal Court of Justice sits at the top of the ordinary courts branch (with a limited exception in Bavaria when only state law is concerned). There are currently 115 Regional Courts and 24 Higher Regional Courts in Germany. Each of these courts has distinct judicial bodies that decide on criminal and civil matters; i.e., the same division, chamber or senate will not be presiding over both civil and criminal matters but instead only hear either civil or criminal cases.

There are no jury trials in Germany. Civil cases are decided by professional judges only (with exceptions for specialized Commercial Chambers), while in some criminal cases two laypersons decide together with one or more professional judges.

To become a professional judge, applicants have to complete a professional legal education consisting of full legal studies at a university followed by the first legal state exam, and a two-year practical training (Referendariat) followed by the second legal state exam. Admission to the German bar as a lawyer generally requires the same legal education as becoming a judge. Only applicants with good results in both state exams will be accepted as judges. Different from other countries where becoming a judge is an opportunity that arises only after a long and successful career in other branches of law, it is not uncommon for good candidates to become professional judges directly after passing the second state exam, usually in their late 20s or early 30s. Judges are hired by the individual states; there is no popular election of judges in Germany. After an initial probationary period (Richter auf Probe), judges are appointed for life, but generally retire at the standard retirement age (currently 67 years). To be promoted to higher courts (Higher Regional Courts and above), tenure at lower courts is usually required and most judges remain at the Local Court or Regional Court level throughout their career. For the federal courts, the Federal Minister of Justice together with a special body, the judicial selection committee (Richterwahlausschuss), appoints the judges. The judicial selection committee consists of the ministers of justice of the German states and 16 members elected by the German Parliament (Bundestag).

Each German court has a schedule to internally allocate cases and other court functions (Geschäftsverteilungs-plan). The court administration establishes the schedule for each year in advance. The schedule specifies which judge will sit with which judicial body (i.e., which chamber or senate), and how cases are distributed among the different judicial bodies, e.g., by the nature of the matter, in alphabetical order, etc. German law requires that the criteria for distribution of cases be abstract in nature and allow the advance determination of which judicial body will hear which case. Accordingly, a claimant has little to no influence over which judge or judges will ultimately decide the dispute and doing pre-litigation diligence on a particular judge or group of judges is highly uncommon.

Cases With Amounts in Dispute Above EUR 5,000

For civil cases, the court of first instance, in general, is the Regional Court for matters with an amount in dispute of more than EUR 5,000 Each civil division of a Regional Court is divided into chambers with three judges each. However, in most cases a sole judge from the chamber will handle the matter. Decisions by all three judges are reserved for cases with particular complexity, or those concerning legal matters of fundamental significance, or certain specialty law matters, or when both parties so request and the chamber agrees.

Appeals against decisions of the Regional Courts go before a Higher Regional Court for questions of law and fact. The civil divisions of the Higher Regional Courts are divided into so-called senates with three judges each.

The decisions of the Higher Regional Court are appealable to the Federal Court of Justice solely on questions of law and only if certain further requirements are met. We will cover the requirements of such an appeal and the relevant procedure in more detail in a future chapter of this series. The civil division of the Federal Court of Justice currently comprises panels nos. I to XIII, each called a senate, as well as a number of panels with special jurisdiction, e.g., over antitrust matters. The senates each consist of seven to nine judges. In general, only five judges of a senate decide an individual case. Each senate has its own area of specialization; e.g., the 2nd senate specializes in corporate law, and the 10th senate specializes in IP matters.

Cases With Amounts in Dispute of EUR 5,000 or Less

For civil cases with amounts in dispute of EUR 5,000 or less, the court of first instance is the Local Court. In addition, Local Courts have a number of special jurisdictions irrespective of the amount in dispute, inter alia, landlord-tenant disputes over residential leases. At the Local Court, a single judge rules on civil cases.

Regarding decisions of Local Courts, the Regional Courts function as courts of appeal. A subsequent appeal on questions of law to the Federal Court of Justice is available if certain requirements are met.

Despite the low ceiling of amounts in dispute, Local Courts play a significant role in disputes involving consumer-facing sectors, and landlord-tenant and traffic law disputes.

Specialized Chambers and Senates

To accommodate particularities of commercial disputes and disputes between merchants, Regional Courts as courts of first instance have specialized Commercial Chambers (Kammer für Handelssachen). These Commercial Chambers consist of a professional Regional Court judge and lay judges with a commercial background. These lay judges are appointed upon recommendation of the local chamber of commerce and industry. Their involvement is meant to ensure that decisions in commercial and merchant disputes consider trade practices and commercial rationale.

To become more attractive as a forum for international commercial disputes, there has been a push to allow for so-called “International Commercial Courts” in Germany. The 2021 Coalition Agreement of the three parties that currently govern Germany aims to establish English-speaking special chambers for international commercial disputes. In order to implement this goal, the German Ministry of Justice in January 2023 published a paper with cornerstones for a corresponding reform of German civil procedure. This reform in particular envisions conducting civil litigation completely in the English language (including the language of the judgment) before the Regional Courts and—on appeal—before the Higher Regional Courts. In addition, the Ministry’s paper contemplates the establishment of special senates at Higher Regional Courts which will act as first-instance Commercial Courts for large-scale commercial disputes. Provided that there is a high amount in dispute (the paper considers a threshold of EUR 1 million), parties can agree to directly call on these special Commercial Courts, i.e., skip the level of Regional Courts.

Since previous pushes for such reform did not progress at the federal level, some German states took action and established specialized “Commercial Courts” or “Chambers for International Commercial Disputes” at the Regional Courts of several bigger cities, e.g., in Frankfurt, Hamburg, Stuttgart, and Mannheim. The most significant feature of these already-established court divisions is that they can conduct hearings in English. Furthermore, they place a focus on enhanced case management. Some of these court divisions allow verbatim hearing transcripts as well as recordings at the parties’ request, which is otherwise uncommon in German civil litigation. With regard to decisions of the Commercial Courts in Stuttgart and Mannheim, appeals are available to similarly specialized senates of the Higher Regional Courts of Stuttgart and Karlsruhe. However, these court divisions are not identical to the International Commercial Courts as envisioned by the federal reform initiatives. Instead, they have to operate within the confines of German civil procedure as it currently stands. In particular, significant elements of the proceedings must remain in the German language, including written briefs and the judgment. Moreover, in most cases both parties need to consent to referring their dispute to one of these special divisions. In many cases, it will be challenging to reach such consent after the dispute has already arisen. So far, parties have been reluctant to employ these special divisions to resolve their disputes. As of 2022, parties have referred only a double-digit number of disputes per year to these special divisions.

Are German Courts Bound by Case Law?

Germany as a civil-law country does not apply the principle of stare decisis. Accordingly, German courts are not bound by precedents in the same way as, e.g., courts in the U.S. are. As an exception to this principle, the decisions by the Federal Constitutional Court are binding on all other German courts.

However, previous decisions of higher courts hold persuasive, yet not always decisive, authority for the lower courts. This is especially true for rulings of the Federal Court of Justice. The lower courts will usually follow on-point decisions by the Federal Court of Justice. Regional Courts also consider rulings of Higher Regional Courts for guidance, in particular the Higher Regional Court in their circuit, which will hear potential appeals against their decisions. Thus, existing case law allows for a more reliable assessment of a case’s chances of success.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that the Federal Court of Justice is willing to overrule its previous decisions if it considers them outdated and no longer appropriate in light of changed statutes or circumstances, and has done so in the past. In some cases different senates of the Federal Court of Justice are even following different approaches to the same legal issue. (There is a statutory mechanism for resolving such disagreements, which is, however, only very rarely used.) The different Higher Regional Courts frequently disagree on how a particular legal issue should be resolved, resulting in inconsistent case law, not unlike a “circuit split” in the U.S. In such a situation, it is more likely that a Regional Court will follow the opinion of “its” Higher Regional Court, i.e., the Higher Regional Court that would hear the appeal. However, in contrast to lower courts in the U.S., German lower courts are not bound to do so and may follow the opinion of another Higher Regional Court or solve the case in a completely different way, although this does not happen often. After all, article 97 of the German Constitution ensures that every judge is independent and bound only by statute (and not by the decisions of the next higher court).

Click here to download this article.

_______________________

[1] Prior chapters will not be updated. There are exceptions and deviations to many of the rules and practices discussed in this chapter that are not individually flagged.

***

The next chapter of this series will describe the course of a civil action in Germany and elaborate on specific details differentiating it from a civil action in commonlaw countries.

Stay tuned for the next chapter, forthcoming in mid-March 2023. In the meantime, your Willkie Global Litigation & Arbitration Team is happy to provide you with further information and advice on these issues.